March 06, 2024

NEWS & TOPICS

Mt. Usu: Living with one of Japan’s Most Active Volcanoes

On March 31, 2000, a series of eruptions began at Mt. Usu in southern Hokkaido. Over the next five months, 60 new craters appeared on and around the mountain, with the ongoing pyroclastic activity and hot mud flows forcing 16,000 residents to evacuate, leaving behind widespread damage.

It wasn’t the first time in living memory that Usu had flexed its muscles. In 1977, an eruption at the peak sent white plumes of smoke 12,000 meters skyward and showered the area with pumice, while activity from 1943 to 1944 saw the creation of a new mountain, Showa Shinzan, rising 402 meters above what until then was an expanse of wheat fields.

Showa Shinzan, and orchards extending to the rear

Today, Mt. Usu and its multiple peaks are part of the Toya-Usu UNESCO Global Geopark (https://www.toya-usu-geopark.org/english/), an area that also includes Lake Toya immediately to the mountain’s north. Together, the lake and mountain open a window on the Earth’s development and have become a rich study ground for volcanologists, while also offering travelers a scenic setting for soothing hot-spring baths and a host of outdoor activities.

Learning About Usu’s Eruptions

As a call at the and adjoining Volcano Science Museum (http://www.toyako-vc.jp/en/) highlights, Mt. Usu hasn’t always been active. Initially formed 20,000 years ago, the peak eventually went dormant for thousands of years, allowing Jomon-era and then indigenous Ainu to settle in the area, before it reawakened in the late 1600s.

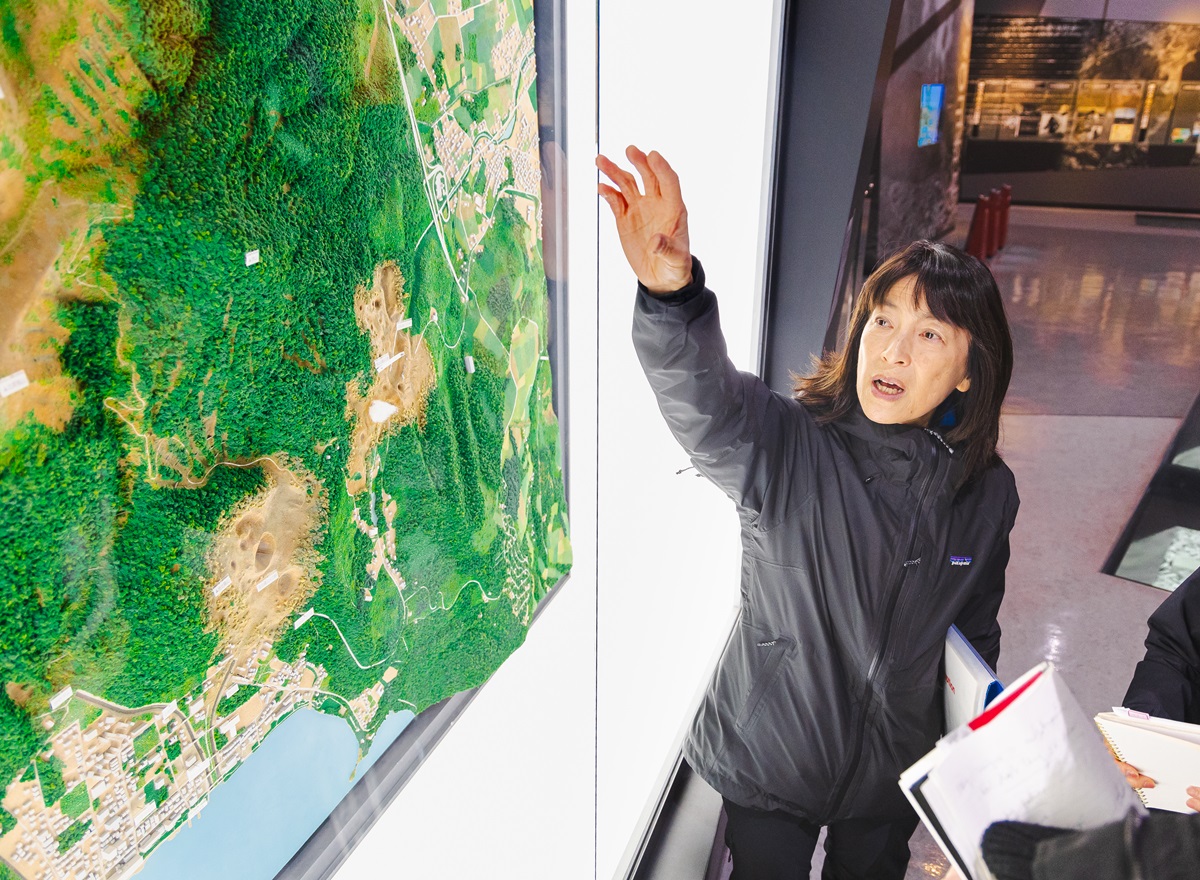

With multilingual exhibits and immersive videos, the visitor center and museum do an excellent job of documenting not just the lake and mountain’s creation, but also local wildlife and topography, as well as giving insights into the events of 1977 and 2000. It’s even better if you come with one of Toya’s Volcano Meisters – guides like Rie Egawa, who have an in-depth knowledge of the volcano and its workings.

“Locals says that Usu never lies. There are always signs that an eruption is coming,” Egawa explains, on a one-day tour that started at the museum and later took in snowshoeing and a ride on the Mt. Usu ropeway (https://usuzan.hokkaido.jp/en/).

“We know that eruptions are likely every 20 to 50 years, but before each one there’s always at least a day of warning tremors. Not wobbling left and right like a regular earthquake, but up and down – a doll wouldn’t fall over, it would jump,” Egawa says. “There are also crustal movements, such as cracks in the road, but another characteristic is that the eruptions aren’t only at the summit; they occur through multiple craters around the mountain’s base, as the sticky magma searches for ways to break through the surface.”

Viewing the Volcanic Land

A ten-minute drive away, we also stop by the Kompira Crater Observation Deck for a first glimpse of how the land here has been marked by millennia of volcanic activity. There are broad views of Lake Toya, a caldera formed 100,000 years ago that subsequently developed a distinctive cluster of peaked islands in its center. Directly in front us is the deep Kompira crater, filled with a frozen pool of water.

Lake Toya seen from Kompira Crater Observation Deck

Kompira Crater Observation Deck

The mudflows from the volcanic eruptions in 2000 carried away a bridge and damaged the public bath facility, and the remains of the structures are preserved.

Taking in the view, Egawa explains that this now-inactive crater was formed during the 2000 eruption, when steaming mud flows destroyed hundreds of buildings (some left as memorials) in the town below. But, as locals say, Mt. Usu also brings good with the bad.

Some 10,000 years ago, for example, a landslide that saw Mt. Usu lose its once-conical peak, reached the sea on the mountain’s southern side, creating a coastline with natural bays utilized by early settlers and rock formations that nurture shellfish, crabs, and other marine creatures. More recently, a series of eruptions in 1910 uncovered Toya’s natural hot springs, which today are a major draw for visitors, with hot-spring baths at hotels and a collection of piping-hot footbaths and handbaths dotted around the town.

“A several-meter layer of well-draining pumice soil brought by recent eruptions, coupled with a reshaping of the land to act as a wind breaker, has also led to ideal conditions for growing fruit like apples,” Egawa adds.

Rie Egawa, Toya’s Volcano Meisters and Hokkaido certified Adventure Travel Guide

Heading in from the cold, we hear more about life in the firing line of an active volcano, when we stop by Restaurant Bayern (https://www.instagram.com/restaurant_bayern_toyako/) for beef stew and a chat with Noriko Yamanaka, whose parents opened the restaurant (close to the base of Showa Shinzan) shortly after the 1977 eruption forced them to relocate from a different part of the area.

“I was born in Toya and grew up here, so I’ve always lived with the volcano. I remember being evacuated, too, but I’ll still live here as long as I’m able,” Yamanaka says. “Even if I lived elsewhere in Japan, it’s a disaster-prone country. Other areas have earthquakes and floods. We just accept that we have eruptions. And we get to live with a beautiful mountain.”

Interview and writing by Jiji Press Ltd. (https://jen.jiji.com/)

Learn more about Lake Toya area (https://www.laketoya.com/en/)

- HOME

- NEWS & TOPICS

- Mt. Usu: Living with one of Japan’s Most Active Volcanoes